On Wednesday 28th October we started again with the first new reading group after the summer. The Topic was “Food Sovereignty/Autonomy and Food Security” and we read two different texts of which you can find a very brief summary below.

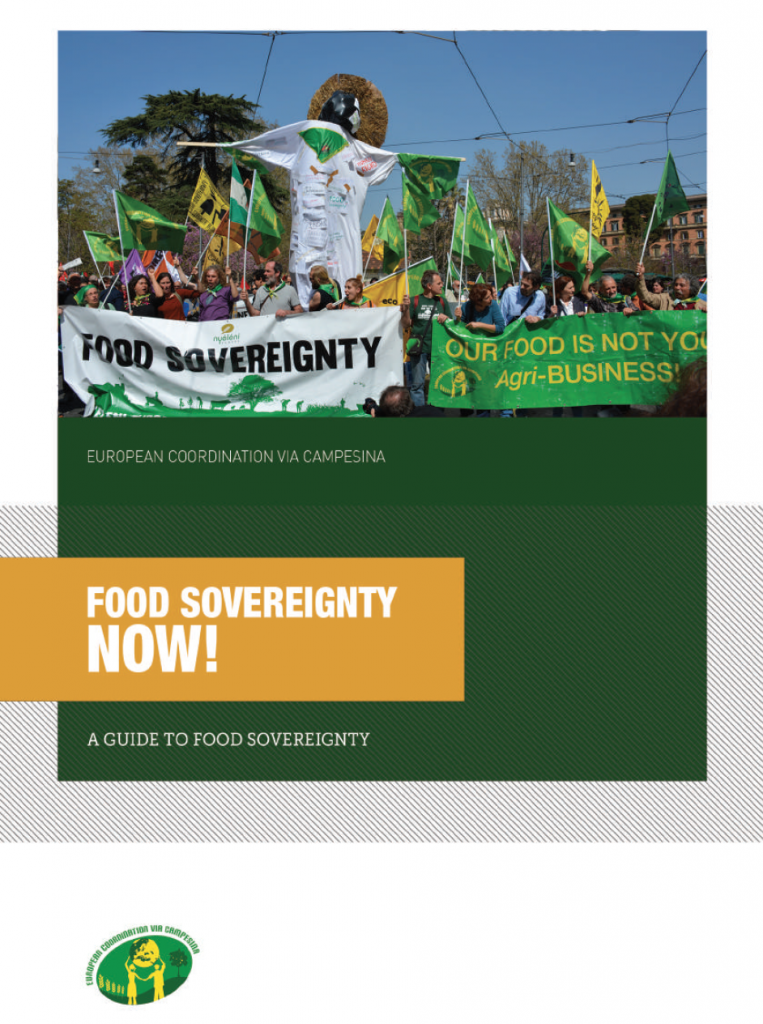

Food Sovereignty Now! A Guide by ECVC

The 1st reading is a comprehensive guide that was put together by the European Coordination Via Campesina (ECVC). The guide defines, describes and analyzes the concept of food sovereignty and how it emerged and developed, from the peasant farmers in a quest to gain back the control over how they feed themselves. Food sovereignty is also presented as a reaction to the term “food security”, which does not take into account where and how the food reaches the consumers. The six pillars of food sovereignty are also included in the text, as well as the Food Sovereignty Movement (FSM) in Europe, criticizing the CAP.

Food Sovereignty, Food Security and Democratic Choice: Critical Contradictions, Difficult Conciliations by Bina Agarwal

The 2nd reading was written by Indian feminist scholar Bina Agarwal. In her article she critically engages with the Food Sovereignty Movement and promises made by the movements. She draws on a lot of practical examples and points out how food sovereignty might not always be what people and farmers choose to go for. She criticizes out how in particular women are not considered sufficiently by the food sovereignty movement as it embraces the family unit but disregards that within a family unit there is a gender imbalance. The impact of climate change on food sovereignty is also analyzed, as well as the important part of the definition, the “democratic choice”.

Reflections on Neocolonialism and European Positionality

People reflected a lot on the diversity of the FSM and re-iterated that as a concept, it does not provide a “one size fits all” solution as people in different places around the world might have different needs. While we discussed whether the fragmented nature of the movement weakens it ability to fight globally centralized forces of the industrial food system, someone pointed out that what unites the movement is that they clearly formulate what agro-food system they do not want and another person raised the point that different strategies make the movement more resilient.

We also discussed whether there is a need to “decolonize” food sovereignty – while actually most of the time food sovereignty itself is regarded as an instrument for decolonizing the food system. People raised the point that when talking about food sovereignty in the Global South from a European perspective we need to always reflect on that position and remember that food sovereignty is authentic only if it comes from the bottom-up as it is a grassroots project that emerged from the needs of various communities themselves. When it is imposed, as Agarwal also describes in one part of her article, it can become dogmatic and reproduce harmful colonial dynamics rather than heal them. Therefore, we need to be aware that food sovereignty, a movement started by peasants in the Global South, does not become prescriptive and imposed by people from a different context onto those who initiated the movement.

The Role of Women’s Rights in the Food Sovereignty Movement

In her article Agarwal criticizes the FSM for prioritizing family farm units while not considering gender imbalances within a patriarchal family unit as well as the struggles women face in regards to access to land, control and resources. Nevertheless, the other reading, the food sovereignty guide by ECVC stresses the importance of female peasants and their particular struggles they face which aim to be addressed by the FSM. Most participants had the impression that the FSM, puts special emphasis on the empowerment of women in their organizational structure and their work. However, as Agarwal shows in her article, in practice women might be drawn towards a different path to empower themselves through financial independence rather than food sovereignty.

Rural-Urban Relation in Context of Food Sovereignty

Agarwal was saying that some people do not want to be employed in the agricultural sector anymore. One of the participants mentions that over the past years there has been a massive rural exodus, and less and less people want to practice agriculture. The discussion on why people do this is very long and complex, we agreed that most often it is not a choice, but moving to cities is perceived as the way to sustain a life in these times, due to lack of access to land, to the market, to an uncertain profitability and to an unfair competition. Under these circumstances, a job in an urban area seems much more viable, especially for the young generation. At the same time, more and more of the peasants and farmers that are left behind in the rural areas are sometimes older, and have been educated about an agricultural system that has to be efficient, profitable and produce what is easy to sell on the market.

Then we discussed about this missing link between rural farmers and the urban consumers, who perhaps have the money for organic produce, but still choose to buy industrial grown food. How do we convince them to choose agroecology so they can practice food sovereignty through their choices (to a certain extent), not necessarily by growing their own food? However, in farmers’ case, as FSM argues for them to have a “democratic choice” of what and how to farm, this might mean that they choose something that is profitable, but not good for the environment as Agarwal pointed out in her article.

Food Justice

Towards the end of our discussion, the issue of food justice was raised, in particular in the context of urban environments. As we started to discuss the concept of ‘Food Deserts’ which are areas in which people have no access to healthy food-neither through land nor through grocery stores, someone pointed towards a more adequate term of ‘Food Apartheid’. This term implies, as opposed to ‘Food Deserts’ that this is not a naturally occurring phenomenon but peoples’ lack of access to healthy food is imposed on them by a system designed to privilege certain groups of people. This is similar to what we discussed previously in the context of why people abandon the peasant life and move to cities, a process that also does not necessarily result out of a deliberate choice but is more than often a consequence of an unfair system.

In this Reading Group we started a discussion on the concept of food sovereignty, the implications and also problematics that arise with trying to put it into practice. Food sovereignty, even though is a global movement initiated by peasants in the Global South, remains context dependent and might mean different things to different people. For people within a European context this also means to critically analyze how a well-meaning global vision of food sovereignty might be blind to situations on the ground as Agarwal points out in her article. Food sovereignty is a “process in action” as the ECVC puts it, constantly evolving from the grassroots, bottom-up.

What could food sovereignty look like in an urban context you might ask? Read here our article on food autonomy and the Lutkemeerpolder in Amsterdam where we also discuss the terminology of food sovereignty vs. food autonomy.

ASEED is a small grassroots collective run mostly by volunteers. We are proud to have the ability to put time and energy into researching topics around agriculture, climate and social justice! However, in order to keep up structures that support this work, along with organizing events and direct actions we need structural funding. During this COVID crisis it is especially hard to find the kind of funding that pays for our financial administration, small budget for coordination and fundraising, and rent for our office.

A great way to help us stay structurally funded is to become a monthly donor! You can do that by visiting the SUPPORT US page on our website, and if you want to get involved in another way please contact us at info@aseed.net.