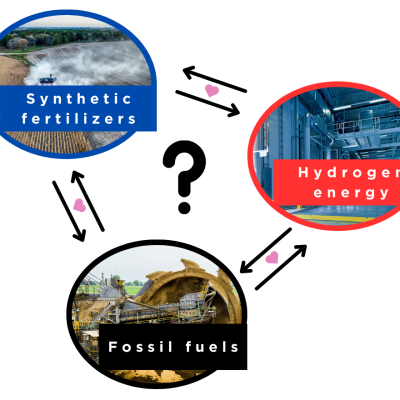

Introduction to the connections between the fossil fuel industry and industrial food system

You might have heard about the industrial food system and that it is bad for the planet in some ways. You most likely have heard about fossil fuels – oil, coal and gas, which are bad for the climate. But how are these two interlinked? Can you really eat fossil fuels?

Let’s take look at the global food system and one of the main ways by which it is tied to fossil gas – nitrogen fertilizers. The producers of it advertise it as the key solution to create a sustainable future for people and the planet. However, this could not be further from the truth. For one thing, it has a devastating impact on our soils, but also the production is fueled by a massive use of fossil gas.

In this article we will briefly sketch out the connection between nitrogen fertilizers and the gas industry by using the example of the YARA fertilizer facility in Brunsbüttel, in the North of Germany.

.

But first, what’s the issue with gas?

If you have reached this article, we probably don’t have to tell you that fossil fuels are damaging to the climate, causing increased temperatures, sea level rise, more extreme weather events and so forth. But there are a few noteworthy details to know about “natural”, fossil gas or methane.

Compared to the other two big fossil fuel sources, gas is a little better when we compare simply how much CO2 is emitted, when we burn it. This is the main reason why the EU and individual countries like it so much – it reduces overall emissions. Or does it?

The process of getting energy out of a fossil fuel doesn’t only include the part where we burn the fuel. It also includes a whole global, highly industrial supply chain. The gas needs to be extracted, transported, transformed, transported again – you get the picture.

Along each of these steps problems occur.

Extraction: Often gas is fracked. Fracking basically means filling the ground with toxic chemicals, which break the rock that stores cracks filled with gas. It pollutes the groundwater and makes the bedrock unstable (earthquakes, yikes!). Because of these major consequences for nature (including humans), there is a moratorium on fracking in Europe. That doesn’t stop fracked gas from arriving here though.

Globally, most gas is extracted in the US, Russia and Iran, often in indigenous areas. Some of it also comes from Mozambique or Argentina, where communities have to deal with the environmental and social consequences of fracking and is consumed in places where this type of extraction would never be allowed. But it’s not only the consumption that happens in the global north, it is also the profits: 9 out of the top 10 gas companies are based either in the US or Europe. Now if this isn’t neocolonial, then what is?

ASEED took action during world water day

Actions took place at Shell in Amsterdam and Pernis

ASEED joined Code Rood in their actions against NAM who extract gas in Groningen

Keep it in the ground!

Transportation: Gas is transported through a variety of ways from pipelines to tankers. To make transport more convenient, it is often cooled down to become Liquefied natural gas (LNG), which basically takes less space, but can still be transported under conditions of more or less normal pressure. energy spent on cooling it??? Not to mention the (fossil) energy it takes to cool it and keep it cool.

Now what’s the problem?

What we call fossil gas mostly consists of methane (or CH4). This by itself is quite a powerful greenhouse gas. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, it is about 84-86 times as powerful as CO2 (over a timespan of 20 years). Luckily for us, it stays in the atmosphere a lot less long than CO2. It remains in there for around 12 years. Unlucky for us, when it breaks down, it doesn’t just go away – it becomes CO2, which stays in the atmosphere for hundreds of thousands of years. When gas is transported, there are always leaks along the way. Methane escapes directly into the atmosphere, has an enormous warming effect until it breaks down and keeps warming the planet. Fracked gas has a leakage of around 12%! For conventional gas this is between 3.6% and 5.4%. Either way, it is too much – switching from coal to gas is only beneficial for the climate, if leakage is below 3.2%.

So even though directly burning gas is better in terms of CO2 compared to its siblings coal and oil, it still has pretty much a similar effect for the climate as they do, because of the way it is extracted and transported. And while ruining the climate, the gas industry is also a massive neo-colonial force.

This is why it is pretty disconcerting that the EU is pushing gas so much. In 2018, the European Investment Bank provided 1.5 million € to the TAP pipeline from Greece to Italy. And this is just one project among hundreds!

But how is this related to my food?

Now that you know the basics about fossil gas – Let’s take a detour and think about Brunsbüttel, a peaceful little town in the north of Germany with a mere 12.000 inhabitants. It is home to small houses with straw roofs, a church, museums, lighthouses and cultural center that serves as a theater and concert hall. It is also home to the single most travelled human-made channel of water: the Kiel Canal (Connecting the North sea and the Baltic sea).

Brunsbüttel is a place with cute houses and a rich culture of trade, but is also a place of heavy industry, where the gas and fracking infrastructure is to be expanded. Now how is this related to the industrial food system?

Von Corinna Sewtz – Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51962924

Von Corinna Sewtz – Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51962961

Von Corinna Sewtz – Eigenes Werk, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=51963720

In order to grow food in the industrial way that is common in Europe, you need nitrogen in the ground so it can fuel the growth process. Luckily for us, there is plenty of nitrogen in the atmosphere – in fact our atmosphere is mostly nitrogen! 72%! Yay! It sits there in combination with itself, doing pretty much nothing. It is inert. However, the type of nitrogen you need for fertilizers is ammonia – nitrogen combined with hydrogen. Now hydrogen unfortunately doesn’t just sit around ready to be used and combined around – we get it from methane! And we have already learnt before, that in the transport of methane, loads of it gets released into the atmosphere. If you want to learn more about nitrogen fertilizers, check out our Nitrogen Fertilizer FAQ.

What’s worse, to do this process, you need pressure around 100 times the pressure of the atmosphere and temperatures between 400 and 500 °C. Guess where the energy to produce this pressure and temperature comes from? That’s right, fossil gas!

So when you eat a cucumber that’s been grown with industrial nitrogen fertilizer, this fertilizer has been made with methane, some of which has escaped into the atmosphere on it’s way to the factory where they produce the fertilizer in a very energy intensive process, the Haber-Bosch process, which releases a whole lot of CO2.

The production and use of synthetic fertilizer alone stands for 10% of global GHG emissions, if the industry’s use of gas and its dependence on fracking and land degradation is taken into account.

This is one of the ways in which the industrial food system and the fossil fuel industry are interlinked, but of course there is also the transport and packaging and preservation of food, keeping greenhouses warm, pesticides, industrial machinery and much much more. And I hope you have a better understanding now of the particular position of the gas industry in this puzzle.

LNG and Brunsbüttel

In Brunsbüttel industries based on neo-colonial exploitation of regions where gas, coal and other products are extracted is concentrated and stands in the way of a just transformation of society.

Companies like YARA, Covestro (which sits in the Bayer industrial park) and Sasol have joined forces to form the “ChemCoastPark” in Brunsbüttel.

- YARA produces artificial synthetic nitrogen fertiliser and thus has a huge gas consumption as both raw material and energy source.

- YARA has nitrogen fertilizer plants all over the world, with the highest concentration in Europe. Their total emissions are 16.6 Million tons of CO2 equivalents. They are the world’s second largest producer of nitrogen fertilizer and the biggest in Europe. If you want to learn more, read our brochure on them here.

- Covestro produces plastics, an industry that also owes its rapid growth to gas expansion as it uses ethane made abundant and cheap by the fracking boom. It’s a spin-off from our friends, the big agro-industrial player Bayer.

- Sasol produces various petrochemical products and has a huge oil consumption, which is partly covered by Wintershall DEA’s Mittelplate North Sea drilling platform.

In this ChemCoastPark these (agro-)industrial players and the German government are now planning a new LNG terminal with a capacity of 8 billion m3/ year – this is a specific case where the gas and agro-chemical industry work together to lock us into a future that is reliant on this damaging fossil fuel.

In 2019, the collective Free the Soil organized an action camp in Brunsbüttel against Yara specifically. This summer the action group Ende Gelände has chosen Brunsbüttel as a target for their mass action days from 29.7 – 2.8.2021. They will block gas infrastructure and rise up against this toxic project. As ASEED, we are joining them, demanding this immediate stop of this project and all new LNG terminals.

If you want to join us, read more about Ende Gelände here and sign up for the bus leaving from the Netherlands using this form.