Temporal references to set the evolution of the local situation:

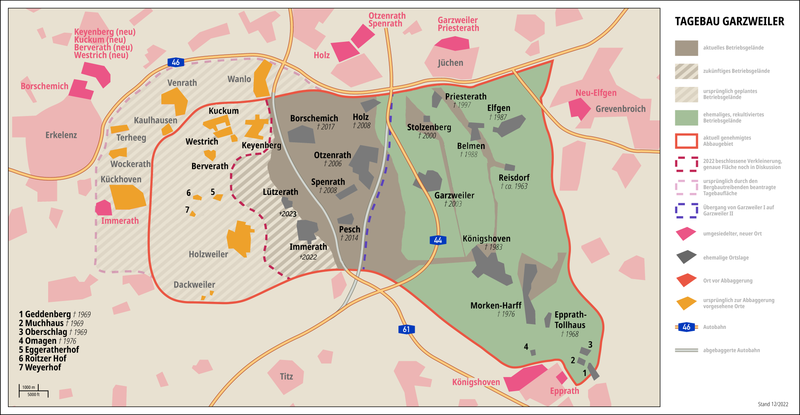

2006: RWE starts digging Garzweiler mine.

2015 : Garzweiler is at the door of Lutzerath. A Klimaat camp is set up and 1st Endegelande action.

2020 : Living area in lützi.

In November 2022, two months before the eviction, I travelled to the village of Luetzerath. I talked to different ZAD inhabitants and gathered testimonies of their choice to occupy the zone, the struggles they face in this decision, and their ideas for societal change.

Some of them wish to remain anonymous, so I mention them with their nicknames to protect their identity.

While walking around the camp in search of someone to talk to, I managed to meet the iconic character of the local resistence: the farmer Eckardt Heukamp.

Here is a transcript of Eckardt Heukamp’s interview, in the yard of his old farm building in Lützerath. With translator and farmer Sonne.

Lava: What feelings do you have when you look at the mine?

Eckardt: I’ve lost two cases now, legally. I can still see the fields, of course, that will always remain in your memory. There are only remnants, two fields are still there, and I still have the third one here in front, a lot’s already been taken away. The anger is still there somewhere, but on the other hand, I can’t change it, or couldn’t change it, and in the end, the power of RWE is stronger than politics. Politicians have not managed to limit RWE’s influence on Lützerath. Maybe they didn’t want to, or maybe they wanted to but couldn’t. The anger is there, but unfortunately, I can’t change it.

Sonne: So you don’t have any land now? That you can work on freely?

Eckardt: I own a farm of 98 hectares, I was growing wheat, barley, canola, sugar, beet, potatoes, and carrots, but now only wheat. I officially only have one more area, and we have now sown on some other areas that we hope to harvest. We hope that RWE won’t take them before next summer so that we can harvest once more. Because then it’s definitely over, that would be the last harvest.

Sonne: And then you have no more land?

Eckardt: Then the land here is completely gone, yes.

Sonne: But you got land from RWE to live on?

Eckartd: No, now I don’t have a new farm. I didn’t get land from RWE, only buildings 4km away, an old property that RWE bought 5 or 6 years ago from a woman that died. There’s a tenant upstairs, there are a few old buildings where I can put my machines and live for 1. 5 years. In the meantime, I have to decide whether to build something new or look for something old, but that’s all problematic because “A”, real estate prices have risen a lot, they’ve doubled in 10 years, and B, building has also become expensive, so it’s hard to find anything. And I also have to think about storing all the machines somewhere, that’s a huge problem.

Sonne: How old are the buildings here?

Eckardt: This side is from 1763, and those are about 100-120 years old.

Sonne: But you’re still here now? So there’s still the possibility of being here, but you’re not here until the eviction, I take it?

Eckardt: Yes, I’ve already moved out, I’m still here with the machines, I should actually have left a long time ago, but I have the impression that RWE doesn’t care, they’re going to clear and demolish it in January or February, that’s what it looks like at the moment.

5 years ago, RWE gave me so-called recultivation land in Buchen, 17km away, to test if I liked it. If I want, I can go with these recultivation fields, but I have not decided to do this. Recultivation fields are composed of old land poured on the pit to fill it again. There is material at the bottom and 1.60-1.80m of soil at the top, not much, a tenth of what is originally here on the land. RWE cultivates it for 10 years and then gives it to farmers, so it’s called recultivated land, or “new land”.

Now I can still decide whether I want to receive a cash settlement or take a recultivated area. Recultivated areas are not too bad, but they have too little humus. There’s only a 1.60-1.80m layer of loess, and they have the huge disadvantage that there is no groundwater where the dredging took place. Even 300m deep, 250m deep there is still no groundwater! I don’t know how long it will take for it to form again. And the old paths of groundwater are being destroyed by RWE that is recently filling up the mine.

If I want to grow specialty crops I need a reliable water supply in order to irrigate. And that is not there! Plus, even if we had water before, we have no right to this water now! RWE does it so that, if you had a well before, then they try to make that possible again, but if they don’t manage then they say “tough luck”! They won’t drill for water somewhere or drive it somewhere or lay pipes for you. That’s the way it is in Germany.

The problem is, let’s say it’s my own land then I still can’t pump groundwater there, because it’s not reachable, and it would be extremely expensive just try to reach it. You can calculate that it costs 1000€ per meter just for digging the hole… Where else could I get water? the Rhine is far away, and I can’t just take water from there, I have to have a permit.

There is now a community of several farmers who have built a sprinkler system with EU subsidies, they have laid a large ring pipe that the farmers will be connected to. But this is not done by RWE, it is funded by the EU. Some farmers who have special crops have joined forces and want to use it in the future.

Every year is different, we don’t know specifics, but the trend is that summers are getting drier and drier. And that is a problem for special crops that are mainly harvested in autumn, carrots, potatoes… The limiting factor is water presence. You can risk it, but at the end of the day, if this point is missing and I invested several thousand euros per hectare, it’s a total failure and loss. Water is no guarantee that you’ll be successful, but it’s a prerequisite.

Lava: Is the soil really good because of humus and water or are there other components? Is the quality of the soil related to the coal?

Eckardt: No, the loess(1) layers have been carried by the wind many, many years ago, and there are only a few areas in Germany with this loess layer – which is called the Börde soil which can be intensively cultivated. I can also farm elsewhere, but these loess soils are characterized by the fact that they retain water and nutrients for quite a long time, which is not the case with sandy soils, because of the grain size. The larger the grain size, the less they can retain water and nutrients. In sand, the grains are fine, but with loess, they are even smaller and you can grow on them well. Also, humus is nothing other than the addition of straw, of crop residues that are left in the soil, and that then slowly raises the humus content, but that takes a very long time until it goes up.

Lava: Was it hard to get these really good popular fields? Was there a competition among farmers to get them?

Eckardt: My great-grandfather bought this land at the beginning of the last century, and I am the 4th generation of the family to farm on these fields. There were Roman and Frankish settlements here, people knew very early on where there was fertile soil and where it made sense to settle. That’s been known for a long time. Many of the roads that we have here, the old country roads were originally Roman roads that were used from early times, and they were renewed and developed again and again.

Lava: Are you planning to relocate the farm? Or do you think it’s too ambitious to start from scratch?

Eckardt: I still have a few years to decide if I want to farm again or if I want to stop. I’m not starting from scratch, but of course, I’ll have to start again. I’m 51 years old and don’t have a farm successor, so what do I do now? Do I work for another 6-7 years and then the biological clock comes, or do I bring this date forward myself and say I’m going to stop and call it a day? I have to build at least 1-2 halls and invest a lot of money in something that only pays off over decades. That’s why it’s such a question because when I commit myself, then the question is, I’ve just built up all of this and then I have to stop and I don’t have a successor. If I had a successor on the farm it would all look different but it’s not that easy to look for a successor. It usually has to be someone from the family. There are inheritance issues.

I also have to say that economically it is becoming more and more difficult for agriculture, in 1972 we had 1050 000farms, now only 260,000, in 8 years we predict that there will be maybe 120,000.You can see from that that the farms have to grow to make it, because whoever wants to stick around has to really get at it or they would have to phase it out at some point.

For organic farming, as well, it is hard to carry on. We have a certain market that takes it up and at the moment, due to the current situation, the decline in organic farming is 40%, which is a lot, not everyone will be able to continue, there are people who earn money with it, and there are other areas where it’s not worth it.

Sonne: That’s why there is solidarity farming because it’s supported by the members, you know that, don’t you? That a certain amount of harvest participants pre-finance the sum needed for a season for so and so many hectares for so and so many vegetables and people, and then it pays for the wages, machines, maintenance costs, and the crops including everything. There’s a hut where the harvest is kept and then the participants can go to different places with it, one 4 kilos, the other 2 kilos – that’s solidarity farming the way I want to do it. That would be amazing here. I’ve seen the Kolawi (collaborative farming project set up in Lützerath) and it’s growing so well! A week ago, there were still courgette plants that looked like they did at the end of summer. I got a good courgette out of it, good soil, yes. Also For the type of farming I want to practice, I wouldn’t need as much water as you do for a monoculture.

Eckardt: Yes, you have to be careful with monoculture, you just do one plant on one field. But you can’t grow beets here, carrots there and grain there either, because that’s not technically possible.

Sonne: Not in conventional farming.

Eckardt: You can certainly go and say you’re making three plots out of a 10-hectare plot, or two plots, but in terms of labour economics that just doesn’t make much sense. Sure, if you grow vegetables, you can do that. You can indeed do that if you want to. But in conventional agriculture, it’s simply a matter of labour economics, you can’t just change every few meters, it’s not possible, the effort is too great.

Sonne: I think I’m noticing that you’ve not really thought about switching to organic farming. Do you have reasons for that? I just wonder why you haven’t thought about it or if you have, why you wouldn’t do it.

Eckardt: I learned conventional agriculture so it’s what I know, and you need space in the market to be able to do something new. It’s no use producing something that I can’t sell. Organic farming is also additional work, I would need people. This is becoming more and more problematic in Germany. I know from vegetable farms that are still harvesting lettuces by hand, there’s one that used to lease land from me, they deliver to Aldi and Lidl, they also used to produce both conventionally and organically and the manager told me years ago that it just didn’t work out with the organic line. The problem is that I would have to gain back the additional costs I incur,t has to be paid for somewhere. And if the customer doesn’t like it enough, it fails… There are plenty of places where this works, but we now have 40% less organic farming in Germany. People don’t have enough money due to the very high price of energy, which means many people don’t have enough money to spend on food, which has already become more expensive, and organic food is even more expensive because it takes more work. And for me, I have to be honest, I can’t do these experiments either. These companies have usually been doing this for 10, 20, or 30 years and have gradually become more and more involved. You can’t just say we’re going organic immediately.

Sonne: Yes, of course, a conversion would take years.

Eckardt: Yes, it takes years, you have to find a market… and you need hands, workers, to do it and that’s a huge problem. I saw that with the strawberry harvest this year and last year, where they couldn’t get enough people either. Machines won’t help, you can do some things with machines, but especially in the vegetable sector, you need manual labour and that is a problem. Because they usually come from abroad, from Eastern Europe, and if they are not there, the farms have a huge problem.

Sonne: Have you done anything for soil development and soil fertility? Did you also have some compost? Did you have any manure? Or did you buy fertilizer?

Eckardt: Well, I always have a mushroom substrate compost. That’s usually produced in the Netherlands. There are big rooms with boxes of straw, and this substrate is put on it, and the mushrooms are grown on it, and you can buy it back and then you have it applied to the fields, That’s about 25-30 tonnes per hectare and of course, that also promotes soil fertility because that is humus. There are nutrients in it, there’s potash in it, and there is a bit of nitrogen in it. This is what I do, and I also cultivated maize last year, or this year, for the biogas plant, and I had the substrates applied this spring. Ultimately, this is biomass that is supposed to replenish the soil, and that’s what it does.

Sonne: And how have you watered so far? Was there a shortage of water? Because RWE has always been almost at the door.

Eckardt: In the last 10 years it has become scarcer and scarcer because in the run-up to mining, when they excavate here, they go put in wells 10 years in advance and then take the water away and the wells are always built as long as the excavation takes place. Also, wells don’t just mean a well, but you have to have an access road, you have to lay pipelines, the field is dug up and you then have problems for years afterward, because the soil is puffy, it is considerably compacted in parts, and then you have economic disadvantages, you can also see that in the harvest. But the massive thing is the lowering of the groundwater because that has a negative effect.

Sonne: It’s crazy that the politicians don’t save this land, which is more fertile than almost any other, and somehow give up on it. I wonder what the future of food should look like here, whether greenhouses will be built like in the Netherlands and then cultivation will be done using hydroponics with lots of chemicals in the water where there is no more soil, so the whole thing works without the influences of soil fertility, weather, etc. whether that is the future of agriculture and agricultural policy here in this country.

Eckardt: Yes, we also already have greenhouses here in the Lower Rhine region, but not as intensively as in Holland. But I think we can also see this here in the commercial land that is being built everywhere. I was just talking to a farmer yesterday at Lake Constance in Friedrichshafen, he’s from the area near Stuttgart where motorways are being built everywhere and commercial areas are replacing farmland that is simply being taken away. It’s the same here, we have more and more industrial estates that are being sold, then businesses go there and the farmland has disappeared. So every day somewhere in Germany we have about 75 hectares of farmland that is taken up and sealed. Every day. In Germany.

Of course, you mustn’t forget that it’s commercial land that brings in a lot of money for the municipalities. Agriculture doesn’t bring that much, the property tax is not that significant for the municipalities, that’s why they try to make commercial land out of it and attract companies to it because that’s all tax revenue.

Sonne: So will there be a future in agriculture here? And if so, how long will that last?

Eckardt: There will still be agriculture, but the number of farmers is decreasing rapidly because the farms have to grow if they want to stay in business and if you always earn the same per unit and the costs increase, you have to see that you get more land to compensate for that, which is difficult. Land can’t be increased indefinitely, or not at all, and if you want to stay in business, then you have to pay high rents for a year to increase the amount of land you have.

I have to say that I tried to defend my farm for a long time, but legally there was nothing I could do, and I don’t believe that RWE would have said, well, if he doesn’t want to go, then let’s leave it. For them, the coal down here is very lucrative, especially now, and that’s why they want to get their hands on the coal, and they don’t consider a farmer.

Sonne: But what happens now if you had refused? Then they would have said there would be no more offer, then we would take it away from you with the police.

Eckardt: Exactly

Sonne: But how can they do that?

Eckardt: It’s very simple, it was a legal procedure. There were two procedures, one was the assignment of the land and the other was the early transfer of possession, the early transfer of possession is already done, and the other one is not yet done. The transfer of possession was earlier, and for that, they come with a bailiff, so you get a letter, and you have to leave the property by the 1st of August. “If you don’t, we’ll evict you, just like the others are evicted”.

Sonne: But what is the reasoning behind it, that they are simply allowed to do that?

Eckardt: They are allowed to.They are saying something about energy, politics has decided, the courts have decided… the courts have said politicians must decide, before those politics said the courts must decide and now politics decided again a few weeks ago in October and it was narrowly confirmed by the Greens at the federal delegates’ conference in Bonn. The Young Greens, the youth, wanted a memorandum to be drawn up, to talk about the matter again, because of the expert reports that they made in 9-12 days to justify demolishing the site… everything has been decided, whether there is still a chance of saving it is very unlikely.

Lava: Is it illegal for us to be here, and the same goes for you?

Eckardt: No, not for staying on the land. I didn’t sell the land, I only sold the buildings with the meadow. The court proceedings weren’t about the land, it was only about the buildings here, the meadow, my parent’s house, and three halls. I’m still the owner of the 98ha, it’s in the land register and I can still decide whether I sell it or not. I have to leave it to the miners for mining use and get a rent for it.

Sonne: That’s still the Nazi law, isn’t it?

Eckardt: Yes, exactly, Hitler enforced this expropriation law in 1935, so that if people don’t sell, they can be expropriated. I can still think about selling the land, I still have the possibility, I’ll get a rent, RWE will pay a rent, it’s called compensation for use.

Sonne: If you decide to sell the land, then you get more money than if they just expropriate you and you get compensation, or how does that work?

Eckardt: Yes, we negotiated things, that was also the reason why I said I couldn’t do anything legally, the lawyers told me clearly that we have no more legal possibilities, it’s over because the court’s decision was very clear, the court said it’s up to the politicians to decide.

Sonne: And then they pay by the hectare?

Eckardt: Goes by the hectare, exactly.

Sonne: And that’s much more than if you sold it privately?

Eckardt: No, no, privately, there is no market anymore, no one buys land that is taken up, they know exactly that they have to give it away, so there is no demand at all, not even for the buildings. You get much less here in the building area than for example in Wanlo, 5 km away, because there’s simply no market here. People are leaving, nothing has happened here for 20 years. These are always voluntary things that RWE does. It’s agreed with the state politicians, but only if you come to an amicable agreement. If you protest and go to court and don’t settle, don’t sell, don’t rent to RWE, you don’t stand a chance, and it’s disgusting that the politicians haven’t done anything for the people. You get very little money for the old buildings. When you build a new farm, you need money because you have to lay pipes, you have to lay electricity, and so on. So RWE gives you a subsidy but you get the minimum, the absolute minimum.

Translated from German to English by Killian.

(1): Loess soil: from German Löss, from Swiss German dialect lösch loose.

A very fine-grained silt or clay, thought to be deposited as dust blown by the wind. Most loess is believed to have originated during the Pleistocene Epoch from areas of land covered by glaciers and from desert surfaces. https://www.thefreedictionary.com/Loess+soil